Menzel’s Extreme Realism

That the exhibition Menzel’s Extreme Realism should have taken place in the Alte Nationalgalerie (Old National Gallery) in Berlin seems obvious. The museum was designed at the beginning of the nineteenth century as a venue for contemporary German artists. In his own time, Adolph Menzel (1815–1905) was recognized as a great artist, and in 1895, there was an exhibition in the Alte Nationalgalerie in honor of his eightieth anniversary.(1) The museum also holds a great number of Menzel’s paintings in its permanent collection. Menzel began painting in the mid-1840s, depicting his surroundings, objects and views from his window. Later he took on grand subjects and events, for example Departure of King William I for the Army, 31 July 1870 (1871). He also took on historical subjects and made himself an expert on the life of the Prussian King Frederick the Great (1792–1786) the subject of several large-scale canvases.(2)

In recent years, not a lot of attention has been paid to Menzel, certainly not in comparison with his nineteenth century German colleague, Caspar David Friedrich. Although Menzel is best known as a painter, he started out as an engraver in the lithography workshop of his father, which he took over when he was only sixteen-years-old after the death of his father. In 1833 Menzel attended the Berlin Academy of Art for a short period, but soon gave it up and taught himself.(3) His background as an illustrator and engraver made him an excellent draftsman, able to capture and visualize objects with such detail and precision. Menzel drew all his life and this is one of the aspects of his work that became clear at the exhibition, which featured his drawings, sketches and small-scale oil paintings from the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin.

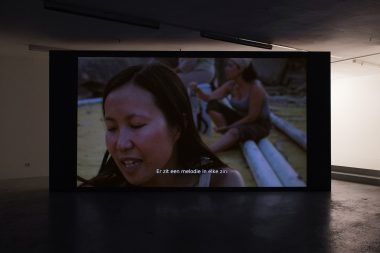

In contrast, it seems highly improbable that the Alte Nationalgalerie would be a venue of the 6th Berlin Biennial of Contemporary Art, nor would it seem likely that Adolph Menzel’s work would be represented in the biennial next to the works of contemporary artists. Still, it was the curator of the 6th Berlin Biennial, Katrin Rhomberg, who initiated this cooperation between the Alte Nationalgalerie and the Berlin Biennial. However surprising it seems that Adolph Menzel was included, Rhomberg mentions that Menzel’s art was in line with her ideas on the theme of the biennial: “what is waiting out there.” According to Rhomberg, reality is always subject to being mere illusion, mere staging, and yet, there is a tendency to cling to it as a seemingly indispensible idea, and there is an ongoing search for authenticity and purity.(4) A lot of the contemporary art that was exhibited at the Biennial focused on different aspects of society, usually in video art, that made the Biennial an overview of the artist’s perspective on the outside world from within the framework of the art world.

However unlikely the cooperation between the Alte Nationalgalerie and the Berlin Biennial seemed, it opened up possibilities to approach and experience the exhibition in two different ways. It can be viewed as a dialogue with the permanently exhibited work of Adolph Menzel in the Alte Nationalgalerie, but also as part of the 6th Berlin Biennial, which focused on how artists deal with the concept of reality from within the art world.

The more obvious way of experiencing the exhibition would be as an addition to the permanent collection. The Menzel exhibition was installed in one of the grand neo-classical halls of the Alte Nationalgalerie, which usually displays many of Menzel’s grand paintings of Frederick the Great. During the exhibition one wall still displayed these large-scale canvases, while the other wall was dedicated to the exhibition. Some of the works presented in the exhibition were studies, which were hung just opposite of the paintings for which they were made. For example, the exhibition contained Menzel’s drawing Worker Holding Shaft of the Casting Truck (with Details) (1872–74) and Worker Washing Himself (ca. 1872–74), both studies of the figures for his painting Iron Rolling Mill (1872–75), which hung on the opposite wall in the exhibition. The exhibition works were hung on a white wall to distinguish them from the permanent display on the opposite wall; however, the distinction between the two was not especially clear.

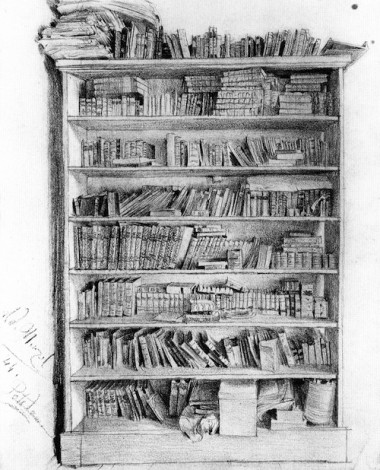

The show also seemed incoherent, lacking a focus on a particular subject or phase in Menzel’s career. The exhibition showed that Menzel had taken a variety of subjects for his studies and sketches, such as his detailed studies of ordinary objects, like Dr. Puhlmann’s Bookcase(1844) or Study of a Bicycle (1890). These subjects ranged from an oil on wood painting called The Artist’s Foot (1876) to the drawing of the Barbarini Faun (1876). However, it was left to the viewer to decide to make the connection between the exhibition objects and the paintings on display.

The exhibition held another dimension when one experienced it as part of the Berlin Biennial. Although the inclusion of the work of a nineteenth century German realist artist might suffer from oversimplification and from far fetched connections when compared to the contemporary art exhibited at other venues of the Berlin Biennial, it is clear that Katrin Rhomberg included Adolph Menzel with specific objectives in mind. Menzel’s inclusion puts the Biennial in a more art historical perspective, and raises questions about visibility, and how art can make the “invisible” visible.(5)

Rhomberg invited the American art historian Michael Fried to curate the exhibition Menzel’s Extreme Realism. Fried based the exhibition on his book Menzel’s Realism: Art and Embodiment in Nineteenth-Century Berlin (2002), which he views as the third book in his nineteenth century realism trilogy that also contains Courbet’s Realism (1990) and Realism, Writing, Disfiguration: On Thomas Eakins and Stephen Crane (1987).(6) In the chapter “Menzel with Courbet and Eakins,” Fried explains that he views Menzel’s work as essentially realist, and compares him to Gustave Courbet and Thomas Eakins by emphasizing that all three are intensely bodily painters, although in each case, this takes on very different forms. Fried explains Eakins as corporeal artist, studying the body’s anatomy in depth, while Courbet’s art is more ontological, questioning the relation of the painter to the artwork.(7)

Adolph Menzel, Dr. Puhlman’s Bookcase (1844). Pencil. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

In Menzel’s Realism, Fried connects embodiment with empathy in Menzel’s art. He does this when discussing Menzel’s sketch Dr. Puhlman’s Bookcase, which was also included in the exhibition.(8) Fried emphasizes how Menzel’s eye for subtle daily objects and his excellent draftsmanship make him capable of showing the viewer objects that would otherwise be taken for granted. At first, it seems that Menzel simply depicted the bookcase as it appeared to him, and the viewer instinctively feels that such a bookcase actually existed. But, as Fried argues, it is not just a detailed depiction of a bookcase with its contents. The wear and tear of the books also shows the invisible, but not ‘unrepresentable’, imprint of Dr. Puhlmann’s touch, his gaze, and his thoughts.(9) Fried touches on art historical discourse, but doesn’t seem to contribute to it or provide new ideas on the subject. The arguments he uses to shed a new light on Menzel seem obvious, although he tries to give us a deeper understanding of Menzel’s work. Still, the sketches seem to remain nothing more than studies.

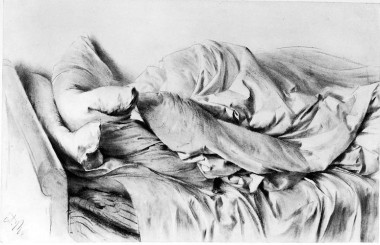

Fried also explains his ideas of embodiment and empathy in the folder distributed for the exhibition. Fried based his aesthetics of empathy on the nineteenth century German aesthetic philosophy, which plays a central role in his interpretation of Adolph Menzel’s most famous drawing, Unmade Bed (ca. 1845) in which the viewer is confronted with a bundle of pillows and blankets drawn with the utmost precision and detail. (fig. 6) Fried makes us aware of the possibility that this unmade bed might not have ever existed in this form, although it of course shows what a good draftsman Menzel was. Fried points out that what makes Menzel’s art ‘bodily’, even if the body is not present, is that in the folds, bulges and contours of the pillow, blankets and sheets, there is still a reference to the form of the recent sleeper.(10) According to Fried, the viewer has these associations because we are not just visual beings, but also have a body and so understand physical form.(11) It seems again that Fried is making an effort to stress a more in-depth explanation of Menzel’s studies, but his arguments seem very apparent and not very renewing. A more interesting point that Fried makes is that Menzel’s work does not just show reality, but that it even produces the reality that it ostensibly records.

Adolph Menzel, Ungemachtes Bett / Unmade Bed (ca. 1845). Black stone and stump on greenish-gray paper. Photograph by Jörg P. Anders. Courtesy BPK; Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Museum of Prints and Drawings, National Museums in Berlin.

However, Fried also makes clear that there is more to Menzel’s art that makes him a realist painter, and makes him worthy of comparison to Courbet and Eakins. He makes this clear in the exhibition folder, and in the chapter “Menzel’s ‘Real Allegory'” where he discusses the artist’s gouache, Crown Prince Frederick Pays a Visit to the Painter Pesne on His Scaffold at Rheinsberg (1861). He compares this picture to Courbet’s famous painting The Artist’s Studio: A Real Allegory of a Seven Year Phase in my Artistic and Moral Life (1855), and to Thomas Eakins’s William Rush Carving His Allegorical Figure of the Schuylkill River (1876–77). Fried argues that Menzel’s gouache is an allegory, because Menzel investigates himself as an artist and shows his capacities as such. The watercolor entitled Menzel in the Pose of Pesne (1861) supports Fried’s idea of Menzel seeing himself as the artist in the picture.(12) However, as the exhibition showed, Menzel quite often used himself as an object of study, for example in Self-Portrait in Abrupt Foreshortening (before 1854). Although Fried is correct in pointing out that Menzel shows his capacities as an artist in a very interesting way, he makes leaps to draw parallels with the two famous allegories of Courbet and Eakins.

Adolph Menzel, Crown Prince Frederick Pays a Visit to the Painter Pesne on His Scaffold at Rheinsberg (1861). Gouache on paper, board backing. Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin.

The erotic female model up on the scaffold with Pesne is very much in contrast with the mannequin lying face down in an awkward position in the left corner of the picture. Fried declares that it would be too simple just to read this dummy that lies forgotten on the ground as a preference for the living model. One can see the mannequin as a distinction that is made in Menzel’s art between the living model and the body as a dead object. In this gouache Menzel makes the viewer aware that he doesn’t just visualise an object in a realistic manner, but that in his art there is liveliness present.(13) Fried draws attention to the sketches Menzel made of corpses, for example Two Dead Soldiers Laid out on Straw (1866) and Corpse of a General from the Period of the Wars of Liberation (1873), and makes a point that even these images drawn with so much detail have a certain morbid liveliness to them.

Fried continues to argue that although Menzel chose a historical subject for his allegory, it is executed in a modern manner. The composition is absolutely a tour de force of vision and technique, and the gouache shows the viewer accurate detail, while giving the feeling of broad freedom at the same time. Menzel has chosen a split second of the prince climbing the unseen staircase, while the violinist on the scaffold is losing himself in his music; higher up on the scaffold, the painter Pesne is engaged in a sexually charged pas de deux with his model–unaware of the prince’s unannounced visit. What makes the picture so modern is that it fills the viewer with expectations of what is going to happen in the next moment.(14) So in a much more complex manner than his sketches of objects, Menzel succeeds in making the viewer anticipate the next scene in this drama.

Next to depicting reality, Menzel also made an extremely compelling physical connection with reality, and even produces the reality that it ostensibly records, which is in line with the theme of Katrin Rhomberg’s Berlin Biennial.(15) The exhibition that was produced by cooperation between the 6th Berlin Biennial and the Alte Nationalgalerie seemed promising. Still, the exhibition has left a lot of possibilities open. The viewer is left to fend for himself and make something of the suggested links and connections with Menzel’s sketches and studies. It shows the work of an artist that is not only capable of drawing objects with extreme precision, but who also has the ability to make the contemporary viewer aware of how reality is formed, constructed and suggested.

(1) Michael Fried, Menzel’s Realism: Art and Embodiment in Nineteenth-Century Berlin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 1-9.

(2) Ibid., 1, 6, 12.

(3) Ibid., 5–6.

(4) Katrin Rhomberg, was draussen wartet/ what is waiting out there, (Berlin : Dumont, 2010), 11–13.

(5) Ibid, 126.

(6) Fried, Menzel’s Realism: Art and Embodiment in Nineteenth-Century Berlin, ix-x.

(7) Ibid., 109.

(8) Ibid., 1–4.

(9) Ibid., 1–4.

(10) Ibid., 41–42, and Michael Fried, “Menzel’s Extreme Realism” in the folder of The 6th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, 2010.

(11) Michael Fried, Menzel’s Realism: Art and Embodiment in Nineteenth-Century Berlin, 35–36.

(12) Ibid.,109, and Michael Fried, folder of The 6th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, 2010.

(13) Michael Fried, Menzel’s Realism: Art and Embodiment in Nineteenth-Century Berlin, 196–197.

(14) Ibid., 185–197, and Michael Fried, the folder of The 6th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, 2010.

(15) Ibid., 185–197, and Michael Fried, the folder of The 6th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, 2010.

This article was published in January 2011 Volume 10, Issue 1 of Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, a journal of nineteenth-century visual culture.